In the folktales and fables of France, animals were never silent observers of human life. They spoke, reasoned, argued, deceived, and reflected the very flaws and virtues of the people who listened to their stories. Through foxes and wolves, lions and crows, storytellers held up a mirror to society, one that exposed arrogance, greed, vanity, and foolishness with sharp clarity and gentle humor.

These animal tales did not exist merely to entertain. They instructed. They warned. And most importantly, they allowed truth to be spoken safely in a world shaped by hierarchy and power. When animals spoke, they could criticize kings, mock authority, and expose human weakness without naming names.

This tradition reached its most enduring literary form in the fables of Jean de La Fontaine, whose Fables choisies drew deeply from oral French storytelling as well as classical sources. Though written for the educated classes of the seventeenth century, the moral logic of these tales belonged to the people. Farmers, children, and courtiers alike recognized themselves in the animals who spoke with human voices.

In these stories, animals are not idealized. They do not represent innocence. Instead, each creature embodies a recognizable pattern of behavior. The fox is clever, persuasive, and patient. The wolf is driven by appetite and force. The lion represents authority and power. The crow, often vain or careless, becomes the victim of flattery. These traits are consistent, allowing listeners to anticipate outcomes even as they enjoy the unfolding irony.

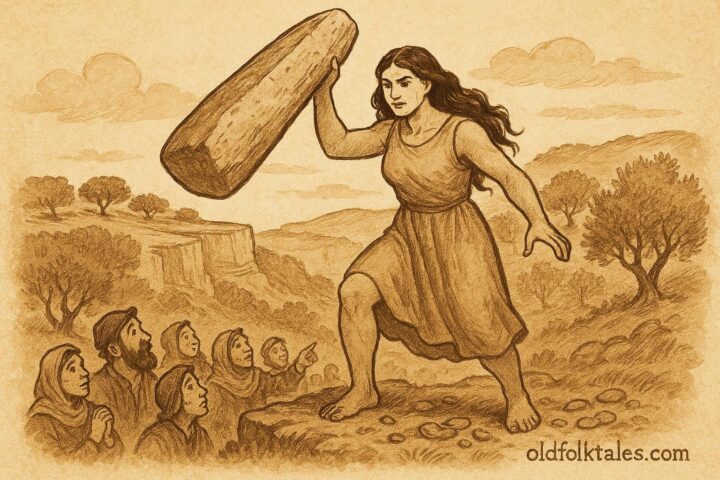

The wisdom of the animal characters lies not in their goodness, but in their awareness. They understand the world as it is, not as it ought to be. The fox succeeds not because it is moral, but because it understands pride. The lion rules not because it is just, but because it commands fear. The donkey suffers not because it is guilty, but because it is powerless.

Through these patterns, French fables reveal a hard truth: the world does not reward virtue alone. It rewards intelligence, awareness, and restraint.

Human folly is the true subject of these tales. Greed drives characters to overreach. Vanity blinds them to danger. Pride prevents them from listening. The animals do not invent these flaws; they simply reveal them. By placing such traits in animal form, storytellers allowed audiences to laugh first, and reflect later.

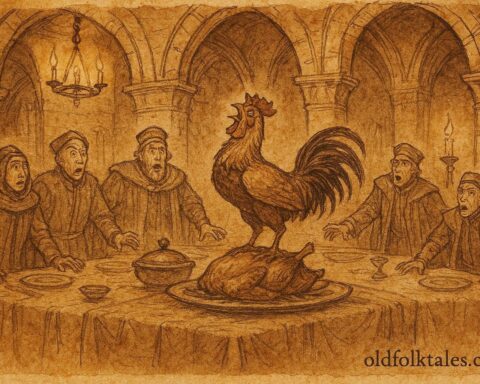

This laughter was essential. The humor of French animal fables is sharp but not cruel. The downfall of a foolish character is often swift and ironic rather than violent. A crow loses its prize because it cannot resist praise. A wolf overestimates its strength. A powerful beast exposes its injustice through its own actions. The lesson arrives naturally, without force.

Unlike heroic folktales, these stories rarely end with triumph. Instead, they end with recognition. The listener understands what went wrong and why. The moral is not hidden, but it is never forced. Wisdom arises from observation.

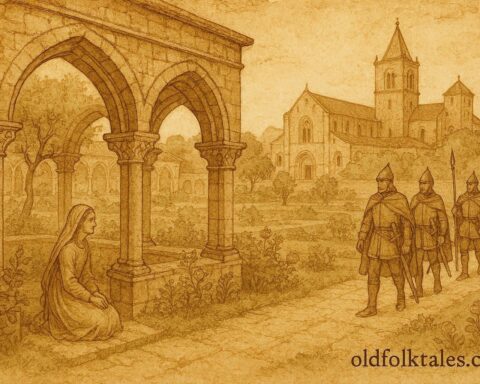

La Fontaine’s fables also reflect a deep skepticism of authority. Kings and judges appear in animal form, often revealing corruption, favoritism, or hypocrisy. Justice bends toward power, not truth. The strong excuse themselves; the weak are blamed. These observations were not revolutionary, but they were honest, and honesty itself was a form of resistance.

Importantly, the animals do not challenge the structure of the world. They navigate it. The fox does not overthrow the lion. It survives beside it. Wisdom in these tales is not idealism; it is adaptation. Survival depends on knowing when to speak, when to remain silent, and when to walk away.

This worldview resonated deeply in a society where social mobility was limited and power concentrated. French audiences understood that cleverness was often safer than courage, and silence more effective than protest. The fables gave voice to these quiet truths.

The lasting power of these animal tales lies in their universality. Though rooted in seventeenth-century France, the behaviors they describe remain unchanged. Pride still seeks praise. Greed still blinds judgment. Authority still defends itself. The animals simply make these patterns visible.

In the end, French animal fables do not ask listeners to become heroes. They ask them to become wise.

Moral Lesson

French animal folktales teach that wisdom comes from understanding human nature. Pride, greed, and arrogance lead to downfall, while awareness and restraint offer survival in an imperfect world.

Knowledge Check

1. Why do animals speak in French folktales?

To safely critique human behavior and social power through symbolism.

2. What traits does the fox usually represent in French fables?

Cleverness, patience, and strategic intelligence.

3. How are powerful figures portrayed in animal fables?

As strong but often unjust, hypocritical, or self-serving.

4. What human flaw is most commonly criticized in these tales?

Pride, especially when paired with vanity or greed.

5. Do French animal folktales promote rebellion?

No, they emphasize survival through wisdom rather than overthrowing power.

6. Why are these stories still relevant today?

Because human behavior and moral weaknesses remain unchanged.

Source & Cultural Origin

Source: Fables choisies (Selected Fables) by Jean de La Fontaine, 1668

Cultural Origin: France (oral tradition influenced by classical sources)