There was a stir across the realms of Belgic fairyland, a rare and restless excitement among the little folk. For ages, fairies had ruled the domains of air, earth, and water, performing marvels no mortal could match. Yet now, the human world was changing fast. Men had begun to fly through the skies, dive beneath oceans, and move swifter than the wind. Their inventions, machines of steam and lightning, seemed to rival the very powers once reserved for fairies alone.

“Soon they’ll be landing on the moon!” muttered a sharp-tongued fairy who detested mankind.

“By and by, there’ll be nothing left for us to do,” sighed another.

“And the children,” cried a third in distress, “will cease to believe in us altogether! No more nursery tales, no more picture books, no more songs sung in our honour. What will become of us then?”

The oldest of the fairies, wise and shimmering like starlight on dew, spoke gravely. “It is dreadful, yes, but what can we do? Just last week, they crossed the Atlantic by soaring through the air. Before that, they voyaged beneath the sea. Men are invading all our domains.”

Then a matronly fairy, known for her deep understanding, nodded knowingly. “There is a reason behind it all,” she said.

“Tell us, please!” cried the younger fairies eagerly.

“It is simple,” the wise one began. “Long ago, humans captured some of our cleverest kin. They bound them, renamed them, and made them work as slaves to power their world. They have stolen our own kind to serve them.”

Gasps filled the air. “You mean, they’ve enslaved fairies?”

“Indeed. They lengthen their own lives by shortening ours,” she replied. “They disguise our kind, giving them strange garments and new names, so that even their fairy mothers would not know them.”

“Can you give an example?” challenged a skeptical fairy, always sympathetic to humans.

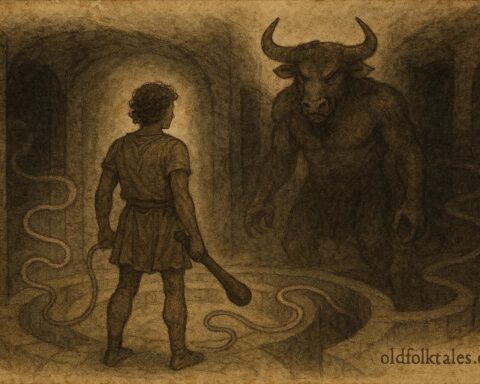

“I can,” said the elder. “There was once among us a powerful spirit named Stoom. He loved to roar and puff, blowing things up just for sport. But men caught him. They trapped him inside their boilers and pipes. Now, they call him Steam. They’ve made bits, gauges, and valves, like bridles for horses, to control him. He drives their ships and engines, pumps their water, ploughs their fields, and lights their homes. Once a free fairy, now a slave of iron!”

A deep hush followed.

“I’ll never be caught,” boasted another fairy, tall and restless, known as Perpetual Motion. “Men have chased me for a thousand years, but just when they think they’ve found me, I slip away again!”

“Don’t be so sure,” said another grimly. “Remember our brother Vonk. He was once a playful spark; he’d rub a cat’s back on a winter’s morning and make the fur crackle with fire. When angered, he’d leap across the sky as lightning! Who would have thought he could be captured? But men caught him, too. First, they trapped him in a jar. Then they pulled him from the clouds with a kite and a key. They made him run through wires to carry messages across the world. Now, poor Vonk dances endlessly between Europe and America through iron cables under the sea. He lights their homes, cooks their meals, scrubs their clothes, and even powers their flying machines. Once the swiftest of fairies, now a prisoner of men!”

Grumbling filled the hall. “Soon they’ll catch us all,” whimpered a lazy young fairy. “We’ll be netted like fish or trapped like rabbits!”

“There will be no fairies left in Belgic land!” wailed another.

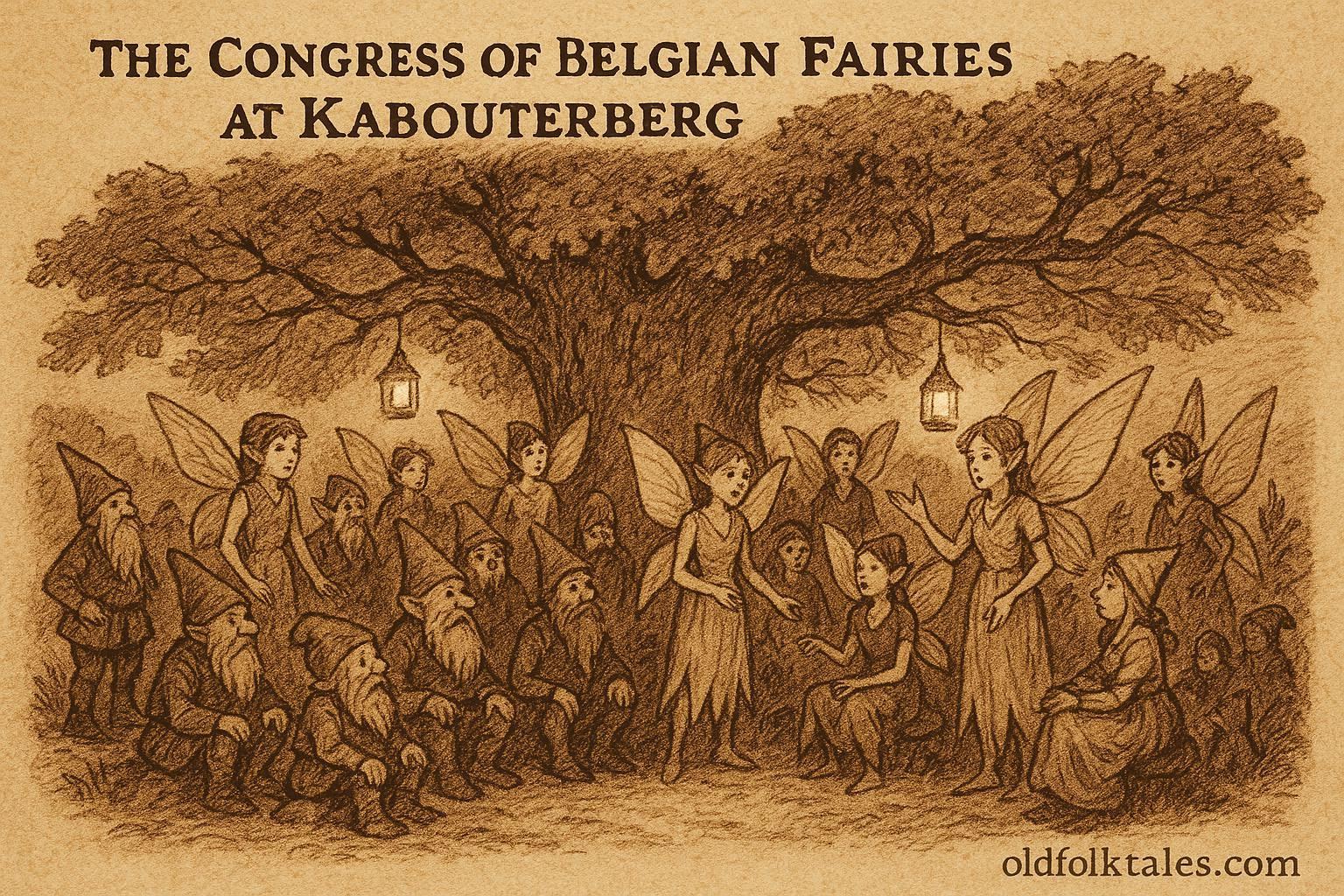

“So,” said the eldest fairy, “we must act before we vanish forever. Let us call a Congress, a grand meeting of every fairy in Belgium, to decide what must be done.”

All agreed. The Congress would be held at Kabouterberg, the Hill of the Kabouters near Gelrode. Invitations were sent to every kind of fairy, from the meadows of Flanders to the hills of the Ardennes, from the zinc mines to the flax fields of Hainault.

And when the day came, they arrived in droves.

First came the Manneken, tiny as thimbles, with twinkling eyes and triangular heads. Mischievous but merry, they loved to play tricks on farmers and servants. Brown as chestnuts, they were beloved by rabbits and called affectionately Mannetje, or Darling Little Fellows.

Then appeared the Kabouters, earth-dwellers and miners, cousins of the German Kobolds. They scrubbed the soot from their faces and wore butternut suits, though they squinted in the daylight.

Next were the Klabbers, the Red Caps, dressed entirely in scarlet, their faces and hands tinted green. Polite and jolly but easily offended, they were said to have the most human temperaments of all Belgian fairies.

Lumbering in last were the Kluddes, clumsy tricksters from the sandy Campine. They could change into old horses but possessed no tongues and could only mutter “Kludde” over and over. When the meeting began, their noisy chanting nearly disrupted the proceedings until the president threatened to throw them out.

The Wappers came too tall, wiry creatures who unfolded themselves like jackknives until they towered above the crowd. They were told to speak politely and not in their usual gibberish.

To maintain order, two giant fairy policemen, Gog and Magog, stood guard, dressed in black, yellow, and red, the colours of the Belgian flag. Their oak clubs, wrapped in ribbons, glowed with authority.

No mermaids came, for there was no salt water at Kabouterberg. No giants or ogres were present either; they had long vanished from Belgian soil. Even the ancient warlock Toover Hek and his wife had not been heard from in centuries.

At the mention of the Dutchman Balthazar Bekker, who denied the existence of fairies, the assembly erupted. Kabouters howled, Wappers clanged pans, and Kluddes bellowed until the president restored calm.

After a long debate, the Congress passed one major decree: a Foreign Fairy Exclusion Law. No fairies from other lands—English brownies, German kobolds, French fées, Scottish sprites, or Irish banshees, were to be allowed in Belgic fairyland. “We must protect our own,” they said. “No cheap labour from abroad!”

When the meeting ended, the storyteller, an American traveller, tried to record all that had been said. But the president ordered all mortals out of the hall, locking the doors. What passed within remained a secret known only to the fairies.

Moral Lesson

Even the smallest beings fear losing their place in a changing world. The tale reminds us that progress should respect the wonders of old, the imagination, nature, and the unseen magic that gives life its mystery.

Knowledge Check

- Who called the Congress of Belgian Fairies?

The fairies themselves, alarmed by how humans had begun mastering powers once exclusive to them. - What is the main theme of “A Congress of Belgian Fairies”?

The struggle between ancient magic and modern human invention in Belgian folklore. - Who was the fairy Stoom, and what does he symbolize?

Stoom represents Steam, symbolizing industrial progress and the loss of natural magic. - Where was the fairy congress held?

At Kabouterberg, the Hill of the Kabouters near Gelrode in Belgium. - Why did the fairies fear men?

Because humans had captured and enslaved some of their kin, using their powers for technology. - What lesson does the story teach about innovation and tradition?

It warns that human advancement should coexist with respect for imagination and nature.

Source: Adapted from “A Congress of Belgian Fairies” in Belgian Fairy Tales (early 20th-century European folklore collection).

Cultural Origin: Belgium (Belgian Folklore)