Beneath the towering peaks of the Swiss Alps, where emerald valleys cradle crystal lakes, there lived a man whose name would echo through centuries, William Tell, the proud hunter and archer of Bürglen. It was a time when Switzerland groaned under the iron rule of Albrecht Gessler, the Austrian bailiff of Altdorf, who demanded not only taxes but submission of spirit.

In the village square, Gessler erected a pole bearing his hat, a symbol of imperial authority. Every passerby was ordered to bow before the hat, as though it were the bailiff himself. The people obeyed, their pride swallowed by fear, all except one. William Tell, strong of arm and steadfast in heart, walked past the pole without bending his head.

Whispers rippled through the crowd. None dared defy Gessler so openly. The bailiff’s soldiers seized Tell and dragged him before the furious ruler. Gessler’s pale eyes glinted with cruel delight as he pondered a punishment fitting for this insolence.

“You are said to be a fine marksman,” Gessler sneered. “Prove it. You shall shoot an apple from the head of your own son. Miss, and both of you die.”

A chill swept the square. Tell’s son, Walter, was brought forth, a boy of tender years but fierce loyalty. Though fear flickered in his father’s eyes, Walter looked up and said quietly, “Do not be afraid, Father. Your hand never fails.”

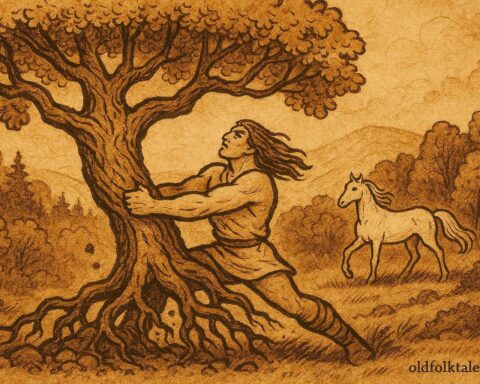

The apple was placed upon the boy’s head. Tell’s bow was handed to him, and two arrows were set in his quiver. The crowd fell silent, even the wind pausing in the pine trees above. Tell raised his bow, his heart pounding like thunder against his ribs. His breath slowed, his vision narrowed. One arrow, one heartbeat, and the shaft flew true.

The apple burst cleanly apart. Walter stood unharmed, a smile breaking across his face. Cheers erupted from the crowd, echoing off the stone walls of Altdorf. But Gessler’s lips curled in suspicion.

“Why two arrows?” he asked, his voice low and venomous.

Tell’s answer rang like steel: “If my first had struck my son, the second would have found your heart.”

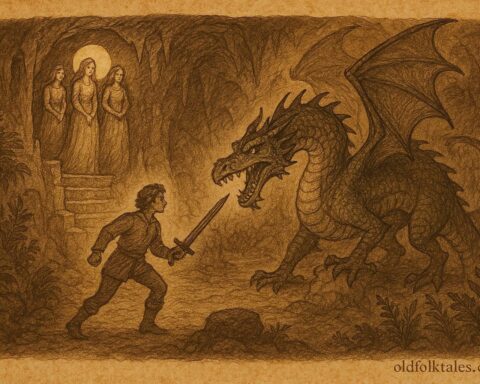

The bailiff’s face blanched with rage. “Seize him!” he ordered. Tell was bound and thrown into a boat bound for Küssnacht, where Gessler planned to imprison him forever. But the Alps have a way of defending their own.

As they rowed across Lake Lucerne, a storm broke, fierce winds and crashing waves threatened to overturn the vessel. The soldiers, terrified, unbound Tell so he could help steer. That was their undoing. With a single leap, he sprang to shore, seized his crossbow, and vanished into the mist.

Later, in the narrow mountain pass known as the Hohle Gasse, Gessler rode through the fog, unaware that his captive was now his hunter. From the cliffs above, Tell waited. He lost the second arrow, the one meant for justice, and Gessler fell from his horse, struck dead by the hand of freedom.

The Swiss rose soon after. Villages rallied, banners were raised, and the foreign oppressors were driven from their valleys. And though many fought bravely, it was William Tell’s defiance, a father’s courage and a man’s refusal to kneel, that lit the first spark of Swiss independence.

Moral Lesson

The legend of William Tell teaches that true courage lies not in violence but in standing firm against injustice. It reminds us that freedom demands both bravery and integrity, and that even a single act of defiance, born of love and conviction, can change the fate of a nation.

Knowledge Check

-

Who was William Tell?

A skilled archer and patriot from Bürglen who became a symbol of Swiss independence. -

What was Gessler’s cruel command?

He forced Tell to shoot an apple off his son’s head as punishment for refusing to bow to his hat. -

Why did Tell carry two arrows?

One was for the apple; the other, he said, would have been for Gessler had his son been harmed. -

Where did Tell finally confront Gessler?

In the mountain pass of Hohle Gasse, where he ambushed and killed the tyrant. -

What does the apple symbolize in the story?

The apple represents innocence and moral trial, testing Tell’s faith, skill, and love as a father. -

What cultural value does this folktale represent in Switzerland?

It embodies the spirit of resistance, national pride, and moral courage central to Swiss identity.

Source: Adapted from Legends of Switzerland by H. A. Guerber (1899).

Cultural Origin: Canton of Uri, Switzerland.